Specific Heat

Today, we explored a key piece of information to thermal energy: specific heat!

We conducted two experiments to learn about what affects the transfer of thermal energy and how thermal energy changes based on certain factors. Here’s what I learned:

1) Three key pieces of information help us find the internal kinetic energy of an object. The temperature of the object, the mass of the object, and the specific heat of the object’s substance. Specific heat describes the amount of energy needed to raise the temperature of one kilogram of a substance by one kelvin. As such, it is described in terms of joules per kilogram per kelvin, or J kg-1 K-1. Every single material has a different specific heat value, and this specific heat value tells us how easy it is to change the temperature of the substance.

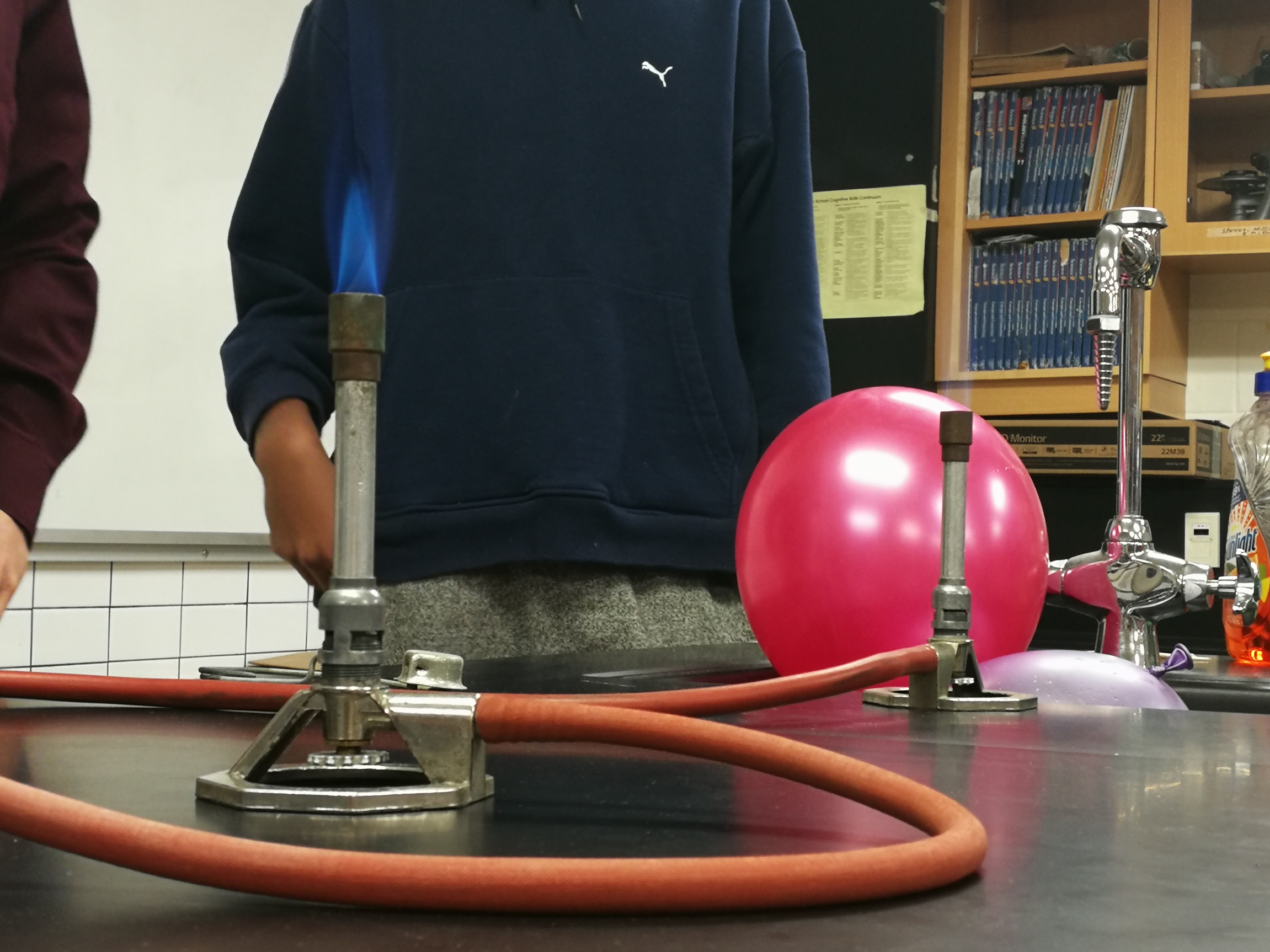

Water is a substance with a specific heat higher than most substances, and we can see that by replacing some of the air in a balloon with water, it heats up (and explodes) much slower than a balloon with just air. Due to water’s high specific heat capacity, large bodies of water help regulate the climate around them. This is why temperatures vary much less near water, and why most of our major cities are found near water.

2) Usually, when calculating thermal energy, we are looking at the change in thermal energy, and so rather than just the temperature, we note the temperature change. The three pieces of information now give us the equation:

Thermal energy (J) = Mass of substance (kg) * Specific heat capacity (J kg-1 K-1) * Change in temperature (K)

Q = mcΔT

3) All objects (matter) equalize at the same temperature of their surroundings given enough time. When this state is achieved, it is said that the objects are in thermal equilibrium. Knowing that two objects at thermal equilibrium have the same temperature, we can use the law of conservation of energy to calculate the mass, specific heat, initial temperature, and final temperature of two bodies who have transferred thermal energy between each other, provided that enough information is known.

The progression of matter to the same temperature is the law of entropy, which states that the world trends towards full disorder, the point at which nothing can gain or lose energy. To see this in real life, we observed a metal disk and a plastic disk. After enough time without disturbing the two disks, their temperatures were measured, and both were found to be about the same at room temperature.

Both the petri dish and the jar cap were at room temperature!

Both the petri dish and the jar cap were at room temperature!

What’s cool about specific heat is that it is something that we have to document as a dictionary of different substances and their specific heats! Here are some questions I have about specific heat:

1) How do we find the specific heat of a mixed solution? Does it simply come down to a weighted average of the specific heat of the substances that make up the solution, based on the percentage of total mass?

2) Is specific heat always constant for a certain substance? Is there any way to change the specific heat?

An intriguing thing that we learned during our experiments was that our bodies feel the transfer of thermal energy, not the temperature of other objects. When we touch the metal, it feels cooler because thermal energy flows from our finger to the metal. When we touch the plastic, the plastic does not conduct heat as well and less thermal energy flows from our finger to the plastic. This is why the plastic felt warmer than the metal, and why having something block the energy transfer, like oven mitts, stops us from feeling the heat of the object.